Dental Health Care

Introduction

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study oral health group led by Professor Wagner Marcenes have provided the scientific evidence for the historical 74th World Health Assembly resolution on “recognizing that oral diseases are highly prevalent, with more than 3.5 billion people suffering from them, and that oral diseases are closely linked to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), leading to a considerable health, social and economic burden.” The Resolution urges Member States to address key risk factors of oral diseases shared with other noncommunicable diseases such as high intake of free sugars, tobacco use and harmful use of alcohol, and to enhance the capacities of oral health professionals. It also recommends a shift from the traditional curative approach towards a preventive approach that includes promotion of oral health within the family, schools, and workplaces, and includes timely, comprehensive, and inclusive care within the primary health-care system. During the discussion, clear agreement emerged that oral health should be firmly embedded within the noncommunicable disease agenda and that oral health-care interventions should be included in universal health coverage programmes.

The perspective of addressing the burden of dental diseases is reinforced in the Sustainable Development Goals agenda, an outline to achieve a better and more sustainable future for humanity that compiles a series of 17 interrelated goals that includes “Good Health and Well Being” as its goal number 3 and the reduction of health inequalities within and between countries as its goal number 10. Untreated dental caries is the single most prevalent human disease in the world with 2.5 billion cases on permanent teeth and 600 million cases on deciduous teeth worldwide [1,2]. Oral conditions accounted for Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) comparably to all maternal conditions combined, hypertensive heart disease, anxiety disorders and schizophrenia, and for more YLDs than 25 of 28 categories of cancer (Stomach, liver and trachea, bronchus and lung cancers ranked higher than oral conditions), cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and mental health other than depression [2]. The burden of dental diseases in childhood and adolescence is mainly due to untreated caries in deciduous and permanent teeth. The number of prevalent cases of periodontal disease and tooth loss is negligeable in those age groups [2]. Dental caries remains a neglected disease [2] and dental health inequities exist [3]. The major outcome of untreated oral diseases in childhood is pain [4,5].

Because of the poor global state of the mouth, the prevalence of oral pain worldwide is high. Two recent systematic reviews [6,7] reported that approximately three out of ten children or adolescents might have experienced toothache in the past. The reported overall pooled prevalence of toothache in children and adolescents was 32.7% [6] and 36.2% [7]. Symptomatic oral diseases cause a major population burden as they impair the ability to concentrate and socially interact. Oral pain impacts the daily activities of individuals, such as eating, sleeping, playing, and attending and paying attention in class and preparing school homework. Furthermore, parents of children experiencing dental pain reported increased expenditure, guilt, and higher workplace absenteeism [8-15]. Therefore, oral pain affects the well-being of children and their families.

Health systems, universities and dental professionals around the world are now challenged to bringing oral health to the centre stage of global health priorities and universities must now be responsive to the 74th World Health Assembly resolution. The main barrier to address the burden of dental diseases is the high cost of providing conventional dental treatment as dental health systems are currently organised, associated to the huge unmet normative need for dental treatment reported above. Instead, reorienting health services by shifting the balance from conventional dental treatment to dental care, including the minimally invasive tooth decay management approach seems to be the prime population health action [2]. Similarly, universities need to shift the balance from teaching conventional dental treatment to up-to-dating teaching evidence-based minimally invasive management of tooth decay to best prepare students for careers in dentistry [16].

Several scientific studies have indicated that the Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) causes less pain, discomfort, and anxiety by comparison with conventional treatments [17]. Low-quality evidence suggests that ART using H-GIC may have a higher risk of restoration failure than conventional treatment for caries lesions in primary teeth [18]. The lower cost of the latter compared to the high cost of conventional dentistry would allow a significant increase in coverage within the same health budget, therefore, reducing the huge global number of untreated dental caries and dental health inequities, without inflicting a major burden on health services budget.

Even adopting the minimally invasive tooth decay management approach, it may be necessary to establish priorities where there are not resources to offer dental care to all. An achievable and realistic goal would be adopting an incremental approach by age throughout allying with the Health Promoting Schools initiative [18] and include dental care in school settings. This starts with the 6-8-year-old cohort, engaging them in the programme in subsequent school years up to adulthood, while adding the new 6-year-old cohort in subsequent years until all school children are enrolled in the programme. All children at starting school age are still free of dental caries in permanent teeth, and up to the age of eight years only a minority may have some decayed permanent teeth, but in an early stage of development. These allow health professionals applying low-cost clinical preventive approaches, such as glass ionomer fissure sealants and detect and manage initial lesions through simple clinical approaches, such as minimally invasive tooth decay management, which prevents further caries progression avoiding the need of complex restorative dentistry in the future. Adopting an age incremental approach starting at the age 6-8-years-old may allow maintaining good oral health for life in a highly cost-effective way. This is because of the low cost of managing dental caries at early stages. Furthermore, this approach does not require expensive technology, specialty training, or elaborate dental health care facilities, thus it can be provided at school settings.

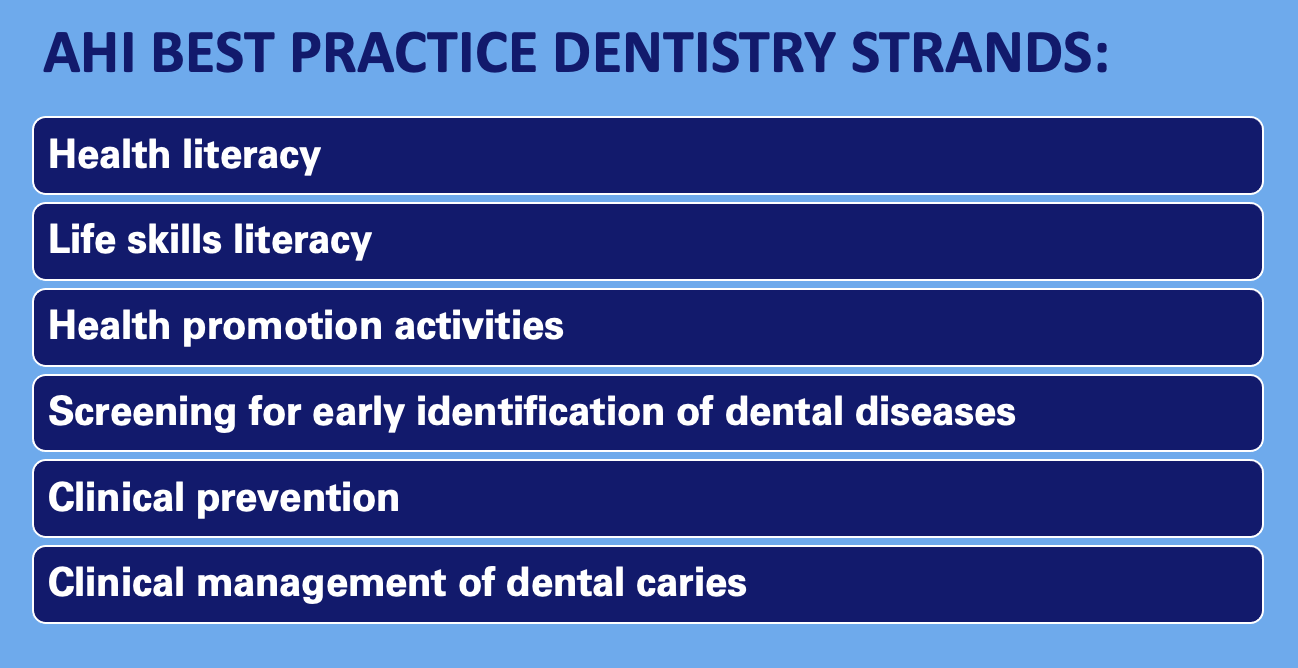

Best Practice Dentistry

Best practice dental care at AHI involves prevention and treatment of current dental diseases. Interlinked health promotion activities are provided. Noticeable, preventing dental diseases improves general health, which facilitates the integration of oral health in the agenda for prevention of NCDs set out in resolution WHA74.5. This is because dental diseases share wider (poor social conditions) and proximal risk factors with non-communicable (unhealthy diets, tobacco use) and communicable diseases (poor hygiene).

Health literacy focusses on the benefits of adopting a healthy diet and good oral hygiene. These are achieved through a set of four school class sessions addressing a single health topic: introduce a topic using e-learning and apply a quiz game (first session); moderate a debate on the topic a week later (second session), moderate a topical group discussion in the following week (third session) and set an individual goal for each topic (last session). A Health Detective game helps to consolidate health literacy. Life skills literacy focusses on the major socio-psychological determinants of health behaviours. It is delivered using the format described above. A health topic (i.e.: sugar consumption) and a life skill topic (i.e.: coping mechanisms) is addressed monthly.

Health promotion activities include implementing the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programme [20] and adds supervised tooth brushing with fluoridated toothpaste at school (see WASH hygiene practices). This assures that all children brush their teeth with fluoridated toothpaste at least twice a day. Good oral hygiene [21,22] and use of fluoridated toothpaste [23] are the most effective preventive approaches to prevent development and progression of periodontal diseases and dental caries, respectively. Healthy promotion activities include includes providing healthy school meals and distributing healthy food to schoolchildren’s families, which addresses the socio-economic barriers to adopt a healthy diet.

Clinical preventive and curative dental care are provided at school setting. Dental care is provided at school setting and offered preferably at breaking time or study time as appropriate and, if necessary due to high demand, during lesson time. In the latter scenario, the children would be excused from attending class in pairs to have dental treatment, while the other children remain attending lessons. All children undergo a screening for presence of untreated dental diseases. AHI acknowledges that proper assessment of caries lesions and the early detection of dental diseases is the foundation to develop evidence based dental care planning. Clinical examination includes several recording categories and allow to compute several oral health assessment indices often used in dental practice for dental treatment planning and in oral epidemiology to assess health status, including the WHO Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT); International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) II and Caries Assessment Spectrum and Treatment (CAST) [24].

Following the screening for dental diseases, dental care at AHI offers application of fissure sealants to the permanent molars and premolars soon after these teeth erupt [25]. Dental care at AHI adopts the principles of minimally invasive management of tooth decay and focusses on preventive dental care based on the interception of disease at an early stage [26], which is the cost-effective modern biological management of tooth decay. Dentinal caries is sealed into the tooth and separated from the oral cavity by application of an adhesive restoration material over the decay. Decay may, on occasion, be partially removed prior to the tooth being sealed. This includes the ART technique, which is the use of hand instruments alone to remove carious tooth substance and the restoration of the cavity using glass ionomer restorative cement, without any injections or drilling. [26, 27, 28]

Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) 38% (44,800 ppm fluoride ions) solution may be used to arrest dental caries in primary teeth [29]. Application of SDF to arrest dental caries is a non-invasive procedure that is quick and simple to use. However, it stains the carious teeth and turns the arrested caries black. It also has an unpleasant metallic taste that is not liked by patients, especially children. The low cost of SDF and its simplicity in application suggest that SDF is an appropriate therapeutic agent for use in school dental health programmes. Reports of available studies found no severe pulpal damage after SDF application. The current literature suggests that SDF can be an effective agent in preventing new caries and in arresting dental caries in the primary teeth in children. It allows definitive restoration to be performed in following years [29, 30, 31].

In addition, dental care at AHI alleviates the suffering caused by severe dental diseases identified in deciduous teeth during the screening for dental diseases. Retained roots, and teeth for which the crowns are unrestorable, or dental nerves (pulps) are exposed with active caries (still progressing) or where the clinician decides the tooth is likely to cause the patient pain or infection are managed by extraction. Of note, children aged 6-8 years will not have severe dental diseases.

References:

1. Marcenes, W., N. J. Kassebaum, E. Bernabe, A. Flaxman, M. Naghavi, A. Lopez, et al. (2013). Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. Journal of dental research, 92(7): 592-597.

2. GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators, Bernabe E, Marcenes W, et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Burden of Oral Conditions from 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):362-373. doi:10.1177/0022034520908533.

3. Schwendicke F, Dörfer CE, Schlattmann P, Foster Page L, Thomson WM, Paris S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2015 Jan;94(1):10-8. doi: 10.1177/0022034514557546. Epub 2014 Nov 13. PMID: 25394849.

4. Boeira GF, Correa MB, Peres KG, Peres MA, Santos IS, Matijasevich A, Barros AJ, Demarco FF. Caries is the main cause for dental pain in childhood: findings from a birth cohort. Caries Res. 2012;46(5):488-95. doi: 10.1159/000339491. Epub 2012 Jul 14. PMID: 22813889.

5. Ferraz NKL, Nogueira LC, Pinhelro MLP, Marques LS, Ramos-Jorge ML, Ramos-Jorge J. Clinical consequences of untreated dental caries and toothache in preschool children. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36(5):389–392.

6. Pentapati KC, Yeturu SK, Siddiq H. Global and regional estimates of dental pain among children and adolescents-systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021 Feb;22(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s40368-020-00545-7. Epub 2020 Jun 16. PMID: 32557184; PMCID: PMC7943429.

7. Santos PS, Barasuol JC, Moccelini BS, Magno MB, Bolan M, Martins-Junior PA, Maia LC, Cardoso M. Prevalence of toothache and associated factors in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2022 Feb;26(2):1105-1119. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04255-2. Epub 2021 Nov 18. PMID: 34791550.

8. Barasuol JC, Santos PS, Moccelini BS, Magno MB, Bolan M, Martins-Júnior PA, Maia LC, Cardoso M. Association between dental pain and oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2020 Aug;48(4):257-263. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12535. Epub 2020 May 7. PMID: 32383273.

9. Goes PSA, Watt RG, Hardy R, Sheiham A. Impacts of dental pain on daily activities of adolescents aged 14–15 years and their families. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66(1):7–12.

10. Naidoo S, Sheiham A, Tsakos G. The relation between oral impacts on daily performances and perceived clinical oral conditions in primary school children in the Ugu District, Kwazulu Natal. South Africa SADJ. 2013;68(5):214–218.

11. Santos PS, Martins-Júnior PA, Paiva SM, et al. Prevalence of self-reported dental pain and associated factors among eight- to ten-year-old Brazilian school children. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214990.

12. Seirawan H, Faust S, Mulligan R. The impact of oral health on the academic performance of disadvantaged children. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1729–1734.

13. Ruff RR, Senthi S, Susser SR, Tsutsui A. Oral health, academic performance, and school absenteeism in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc American Dental Association. 2019;150:111–121.e4.

14. Ribeiro GL, Gomes MC, de Lima KC, Martins CC, Paiva SM, Granville-Garcia AF. Work absenteeism by parents because of oral conditions in preschool children. Int Dent J. 2015;65(6):331–337.

15. Gomes MC, Clementino MA, Pinto-Sarmento TCDA, Martins CC, Granville-Garcia AF, Paiva SM. Association between parental guilt and oral health problems in preschool children: A hierarchical approach. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):854.

16. Frencken JE. Atraumatic restorative treatment and minimal intervention dentistry. Br Dent J. 2017 Aug 11;223(3):183-189. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.664. PMID: 28798450.

17. Frencken JE, Flohil KA, de Baat C. Atraumatic restorative treatment in relatie tot pijn, ongemak en angst voor tandheelkundige behandelingen [Atraumatic restorative treatment in relation to pain, discomfort and dental treatment anxiety]. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2014 Jul-Aug;121(7-8):388-93. Dutch. PMID: 25174188.

18. Dorri M, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Walsh T, Marinho VC, Sheiham Deceased A, Zaror C. Atraumatic restorative treatment versus conventional restorative treatment for managing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Dec 28;12(12):CD008072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008072.pub2. PMID: 29284075; PMCID: PMC6486021.

19. WHO/UNESCO. 2021. Making every school a health-promoting school: Global standards and indicators for health-promoting schools and systems. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

20. UNICEF. 2016. Strategy for water, sanitation, and hygiene 2016-2030. New York UNICEF Programme Division.

21. Kumar S, Tadakamadla J, Johnson NW. 2016. Effect of toothbrushing frequency on incidence and increment of dental caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 95(11):1230-1236.

22. Lertpimonchai A, Rattanasiri S, Arj-Ong Vallibhakara S, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. 2017. The association between oral hygiene and periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Dent J. 67(6):332-343.

23. Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Sheiham A, Logan S. 2003. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(1):Cd002278.

24. Gudipaneni RK, Alkuwaykibi AS, Ganji KK, Bandela V, Karobari MI, Hsiao CY, Kulkarni S, Thambar S. Assessment of caries diagnostic thresholds of DMFT, ICDAS II and CAST in the estimation of caries prevalence rate in first permanent molars in early permanent dentition-a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2022 Apr 20;22(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02134-0. PMID: 35443630; PMCID: PMC9022274.

25. Mickenautsch S, Yengopal V. 2016. Caries-preventive effect of high-viscosity glass ionomer and resin-based fissure sealants on permanent teeth: A systematic review of clinical trials. PLoS One. 11(1):e0146512.

26. Innes NP, Manton DJ. Minimum intervention children's dentistry - the starting point for a lifetime of oral health. Br Dent J. 2017;223(3):205-213. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.671

27. Nigel Pitts and Domenick Zero. White Paper on Dental Caries Prevention and Management A summary of the current evidence and the key issues in controlling this preventable disease. https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2016-fdi_cpp-white_paper.pdf

28. Desai H, Stewart CA, Finer Y. Minimally Invasive Therapies for the Management of Dental Caries-A Literature Review. Dent J (Basel). 2021 Dec 7;9(12):147. doi: 10.3390/dj9120147. PMID: 34940044; PMCID: PMC8700643.

29. Gao SS, Zhao IS, Hiraishi N, et al. Clinical Trials of Silver Diamine Fluoride in Arresting Caries among Children: A Systematic Review. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2016;1(3):201-210. doi:10.1177/2380084416661474.

30. Contreras V, Toro MJ, Elías-Boneta AR, Encarnación-Burgos A. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride in caries prevention and arrest: a systematic literature review. Gen Dent. 2017;65(3):22-29.

31. Oliveira BH, Rajendra A, Veitz-Keenan A, Niederman R. The Effect of Silver Diamine Fluoride in Preventing Caries in the Primary Dentition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Caries Res. 2019;53(1):24-32. doi:10.1159/000488686